Truth is God’s Faithful Saving Action — John 18:33b-37

In her interpretation of John 18:33b-37 Kathleen Rushton contrasts Jesus and Pilate as images of kingly power and truthful relationships.

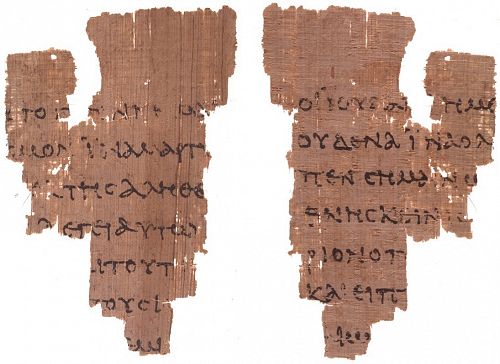

The text of the gospel of John has been handed down to us through fragments and manuscripts such as Papyrus 457 (P52). This fragment measuring 8.9cm x 6 cm at its widest was found near the River Nile. The production, reproduction and transmission of bibles have been possible through the interconnection of plants, minerals, the environment and climate. The document P52 exists through this interconnection. Its material substance comes from a large wetland papyrus plant which grew by the Nile. Human hands harvested its fibres to produce paper-like papyrus on which Greek letters were inscribed with pen and ink, made from wood, minerals and natural dyes. Through writing and reading, human bodies, breath and language were involved in handing on the oral and written tradition. We now touch, smell and see the paper of our bible.

There is writing on both sides of P52 the oldest known piece of the New Testament, dated to 125-150 C.E. It is from a codex — a sewn and folded book. On the front side (recto) are parts of seven lines from John 18:31–33 and the reverse side (verso) contains parts of seven lines from Jn 18: 37–38. In those verses, Jesus is cast as king in the trial scene and there is an exchange about the truth. I shall relook at the notion of king and truth for this scene will be proclaimed in the Liturgy of the Feast of Christ the King.

Role of governor

The trial of Jesus is structured in seven brief scenes (Jn 18:29–32; Jn 33-38a; 38b-40; Jn 19:1-3, 4-7, 8-11, 13-16). Pilate is the key person in each scene, moving back and forth between where Jesus is held inside the Roman praetorium and “the Jews” in the outer courtyard. There are three reasons for stressing Pilate’s weakness and insecurities when speaking of his role in Jesus’ death.

First, the trial is read from the perspective of blaming “the Jews” for the death of Jesus. The context is treated as a religious dispute. However it casts it in an ethnic framework rather than in its imperial and political realities.

Second, the religious perspective can obscure the imperial and political background of the negotiations. The Jerusalem leaders as allies of Rome are the ones seeking to get rid of Jesus. The Jerusalem elites gathered around the temple are the leaders in their society, who wield power as allies of Rome and are also dependent on and subordinate to Rome. Their alliance is distinct from the Jewish population of Jerusalem who, in John, do not demand that Jesus be crucified.

Third, no consideration is given to how governors functioned in the Roman hierarchal, imperial system which had at its core small allied elites. Pilate is identified with the praetorium (Jn 18:28) which is derived from a title of a Roman official (praetor) who had military and judicial duties. Men appointed as governors came from the Roman aristocracy. Their families usually had wealth based in land as well as being well-connected with other civilian and military elites. It is likely that Pilate came from this elite ruling class.

The role of governors included: settling disputes and keeping order, collecting taxes, responsibility for fiscal administration, engagement in public works and building projects, commanding troops and administering justice — including the power to put people to death.

Pilate had seized money from the temple treasury to build an aqueduct. Ancient writers, like Philo and Josephus, record that he ruled with an iron fist and was removed from office by the Roman authorities because of his cruelty. In writing about governors, Josephus uses the image of governors as “bloodsucking flies” and attributes this image also to Tiberius, the emperor when Pilate was governor of Judea.

Jesus as king

Against the background of the powerful role of the Roman governor the portrayal of Jesus as a different kind of king is accentuated in the trial (13 times). Jesus has been addressed as king (1:49; 6:15; 12:13, 15). The Greek word for “king” (basileus) was used of the Roman emperor so Jesus is presented in an opposing relationship to the emperor (basileus) and his representative, Pilate. Jesus speaks to Pilate. (In the other three gospels he is silent.) When Jesus asserts twice that his basileia (empire) “is not from this world,” again he is set in opposition to Rome. The term basileia Jesus used was the word for the empire of Rome. This shows that the issue is about power and sovereignty and how power and sovereignty are to be expressed. Jesus is a very real political threat to how Rome and Jerusalem order the world.

The origin of Jesus’ basileia is central. God creates and loves the world — Jn 1:10; Jn 3:16; Jn 15:18–19. Jesus’ basileia is from God (Jn 3:31; Jn 8:23, 42; Jn 16:28). Jesus reveals God’s claim over all human lives and structures. It is a very political claim to establish God’s basileia over all — including Pilate’s basileia. There is no armed resistance from Jesus’ followers (Jn 18:37). The word Jesus uses for his followers is also used of those (usually translated as “police”) sent by the temple elite to arrest him (Jn 18:3, 12, 18, 22; 19:6). The sense of this word is to work with another as the instrument of that person’s will. While the world of Pilate’s empire and his Jerusalem allies is based on coercive power and domination, the mission of Jesus is to testify to the truth.

Truth – God’s faithful saving action.

Truth, a key word in John, needs careful defining. Jesus describes himself as “truth” (Jn 8:32; 14:6). The term “truth” is often taken to mean “genuine” or “real.” Much has been made of this aspect philosophically. In the biblical tradition, however, truth often means “faithfulness” or “loyalty” in that one is faithful to one’s obligations and commitments. The Hebrew term for “truth” or “true” (‘emet), is often translated as “faithfulness.” It is applied to God who acts “truthfully” when God is faithful to God’s covenantal promises by showing hesed to save the people. Hesed is the word for “mercy” — often translated as steadfast love or loving kindness. In Exodus 34:6, for example, God is described as “abounding in mercy hesed and faithfulness ‘emet.

When Jesus declared that his mission is to testify to “the truth”, he is telling Pilate that he witnesses to God’s faithfulness in saving the people. Jesus witnesses to the truth (Jn 3:33), declares he is the truth (Jn 14:6) and reveals that God is acting faithfully to save the world God loves (Jn 3:16-17; 8:14-18). Truth, then, refers to God’s faithful saving action. Jesus also explains to Pilate that the characteristic of those who “belong to the truth” is that they listen to his voice as do the sheep in the Good Shepherd parable and Mary of Bethany. Pilate does not listen. He does not “see” who Jesus is or his origin or his mission.

Empire today

How do we reframe the Feast of Christ the King, a title we may find uncomfortable today? What is the empire today? How is it opposed to the basileia of Jesus? Pope Francis is calling on the world to rethink and develop economic and social progress that is in harmony with Creation. He notes that it is “easy to accept the idea of infinite or unlimited growth which proves so attractive” (Laudato Si' par 106) and “compulsive consumerism” (par 203). If truth refers to God’s faithful saving action and if as disciples today we are called to be faithful to our obligations and commitments, how will we participate in the mission of God with Jesus?

Published in Tui Motu InterIslands, Nov, 2015.

Gallery