Reconnecting with Our Neighbour — Luke 10:25-37

Katheen Rushton writes about the Parable of the Wounded One, Luke 10:25-37, as stretching our idea of neighbour to include all of creation.

In Luke 9:51 Jesus “turned his face to journey (poreuesthai) to Jerusalem” (Lk 9:51) and for the next 10 chapters we read about Jesus journeying with his disciples (9:51‒19:27). The verb “to journey” is used frequently (Lk 9:53, 56-57, 10:38, 13:31, 33; 17:11; 19:28) and there are many references to being on the move.

Journey — A Way of Living

Jesus is teaching and instructing his disciples on a journey as they walk in Earth. Journeying becomes a metaphor for a way of living that shapes the meaning of discipleship in Luke’s community. The Lucan community lived probably around 60-85 CE in a Greek-speaking area of the Roman occupied world — we don't know the exact location.

Jesus presents ways or paths that lead to authentic discipleship as he moves from place to place with the disciples. He critiques aspects of social and cultural behaviours which are contrary to the way of God. As Australian biblical interpreter Michael Trainer writes, Jesus critiques behaviours that keep people “oppressed, divided and out of harmony with themselves and the natural world in which they live.”

“And Who Is My Neighbour?”

Although Jesus addresses three groups on the way — his disciples, the crowds and his adversaries — he is also addressing Luke’s community and all the generations since, including ours today.

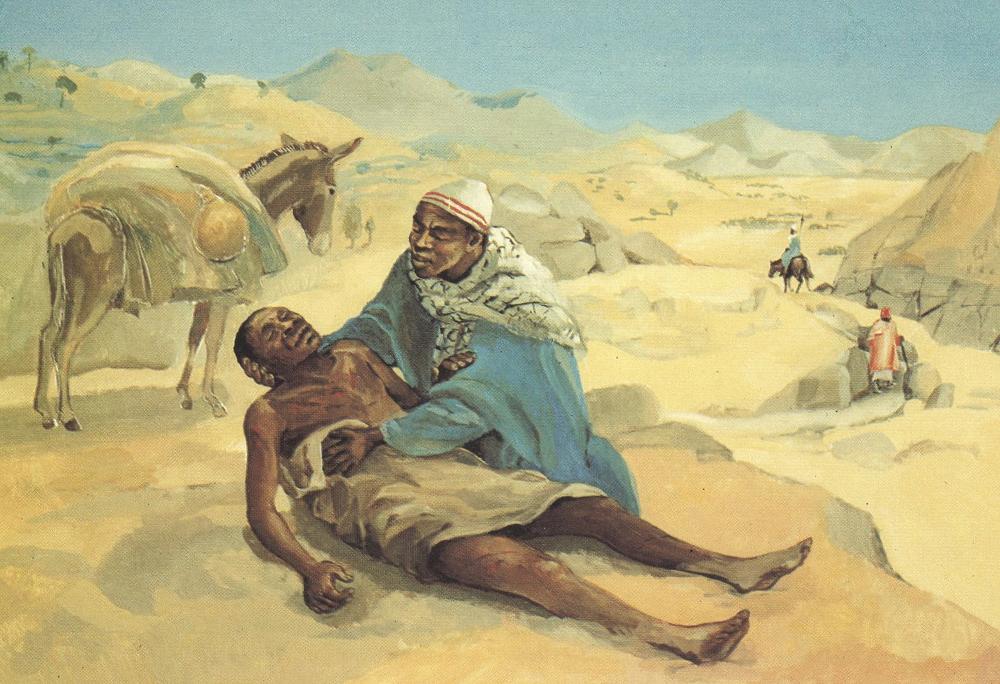

Jesus tells parables among which is the Parable of the Wounded One (Lk 10:30-37). This parable illustrates the great commandment of the Torah concerned with loving God “with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind and your neighbour as yourself” (Lk 10:27).

Shift of Focus on Characters

Until the 19th century the parable was known as the “Parable of the Man Who Fell among Bandits”, where the emphasis was on the wounded person — as it is in the structure of the parable. In the early Church, interpreters identified the Samaritan as Jesus. Today we know the story as the Parable of the Good Samaritan, even though Luke does not use the adjective “good”. The name change to “Good Samaritan” emerged in the 19th century when European society and the Church had increased in wealth and affluent people dispensed “charity” to the poor and needy. They thought of themselves as “good” people and identified with the “good” Samaritan.

Humanity

The parable begins and ends by focusing on a person (anthrōpos) — the Greek word is a generic term for the humanity of a person, not a “male” or “man”. The use of anthrōpos encourages us to see the Wounded One not as an individual but as representing humanity and the human condition. The word has already been used in Luke’s healing stories and will reoccur (Lk 12:16; 14:2, 16; 15:11; 16:1, 19; 19:12; 20:9).

Journeying from Jericho to Jerusalem

The parable says the “person (anthrōpos) was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho” (Lk 10:30), a

30 km descent from around 750 metres to 250 metres, on a road well known for brigands. The wounded one is described as having been beaten, stripped naked and left

half-dead.

Three people come along the road and see the beaten one. Jesus’s listeners would recognise and expect the three to represent the three classes of people who served in the Temple: priests, Levites and laypeople. They heard that a priest and then a Levite passed by without stopping, so they would have expected that the third person, a layperson, would be the one to act. But no! The hero is not a Jewish layperson but a Samaritan, a person from a group they despised.

A Samaritan

A Samaritan journeying on the way “came near him … saw him … was moved with compassion (splagnizomai) … went to him (Lk 10:33-34). The verb splagnizomai meaning “having a heart moved with compassion” comes from the Hebrew word for womb.

Here, and as elsewhere in Luke and Matthew, the Samaritan engages in a threefold pattern: (1) a description of need, (2) a person is described as “having a heart moved with compassion”, and (3) something must be done to address the need the heart has felt. In this threefold pattern is found qualities of discipleship: to see, judge and act. The parable, as Michael Trainer emphasises, highlights the interconnection of all creation —vegetable, animal and human.

Harmony of Creation

As we reflect on this parable, we can become aware that the Samaritan becomes neighbour to the wounded one by bringing together God’s intended harmony and interconnection of all aspects of creation in a compassionate and holistic way. In bandaging the wounded person’s wounds, the Samaritan uses Earth’s gifts of wine and oil in the healing process. The bandages would have been made from cotton.

The animal world is involved in the healing process — the Samaritan put the person on “his own beast (ktēnos)”. Here Luke uses a word that his Greek speakers would recognise as derived from a cluster of words such as creator, creature and creation which come from the verb, to create (ktizō). The Samaritan brings the wounded person to an inn. The innkeeper continues human care with the material support that the Samaritan provides. In doing so, the Samaritan risks his own life by taking the wounded person to an inn in a Jewish area.

The cost and risks taken by the Samaritan point to Jesus. Asking the question: "To whom must I become a neighbour?" will cost disciples. We can choose to pass by or we can cross to the other side — each person in their woundedness is neighbour to another wounded person and wounded Earth.

The parable asks more from us than being “good” and “charitable” like our 19th-century forebears. It demands that we expand our sphere of vision from the individual to the community: a journey of awareness away from “man” and towards anthrōpos; from wounded one to wounded world. Pope Francis reminds us in Laudato Si’ that “these ancient stories, full of symbolism, bear witness to a conviction which we today share, that everything is interconnected” (LS par 70).

“Everything is related, and we human beings are united as brothers and sisters on a wonderful pilgrimage, woven together by the love God has for each of [God’s] creatures and which also unites us in fond affection with brother sun, sister moon, brother river and mother earth” (LS par 92).

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 305 July 2025: 24-25