An Ecological Reading of Matthew’s Gospel 5:1-12

ELAINE WAINWRIGHT provides a fresh approach to understanding the Beatitudes in her interpretation of Matthew 5:1–12.

When I first turned my ecological lens to the Beatitudes, Matthew 5:1–12, I imagined that they would be an almost impossible challenge — we have read them from an exclusively human-centred perspective for so long. How surprised I was to find new wisdom opening up in front of me.

Notice the Time

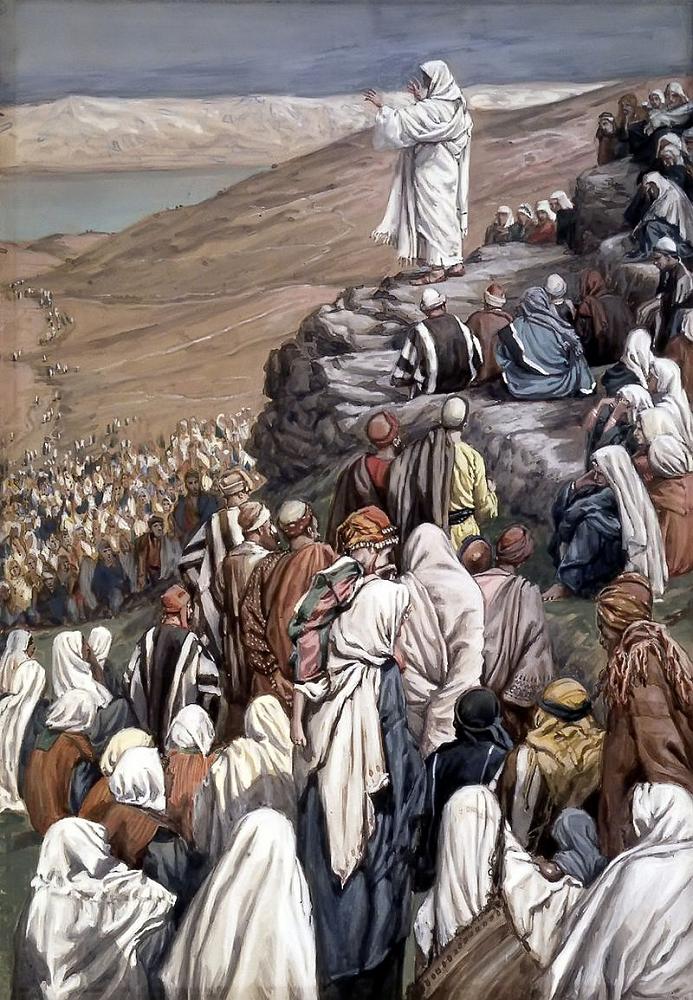

The text of Mt 5:1–12 opens at the precise moment when Jesus sees the crowd. The gospel writer draws attention to a point in time: it is a particular day which may seem like any other day and any other time. But on this day, crowds are gathering and Jesus goes up the hillside, sits down on the ground and teaches. Our encounters in the gospels with Jesus Emmanu-el are always grounded in time, and this invites us to be attentive to the particularity of days and moments.

Notice the Place

As well as alerting us to the specificity of time, the opening verse of Mt 5:1–12 draws particular attention to place: Jesus went up the hillside. Place, like time, is something we can overlook in our gospel story. However, the evangelist makes it significant by mentioning it early and up front. There is an interrelationship of time and place — the day, the crowds, Jesus, the hillside and the final words of the opening verse — which grounds what follows: “and he taught them from there” (Mt 5:2). There are no teachings of Jesus which stand apart from time and place.

Blessed Are the Truly Humble

Jesus, the preacher of beatitudes from a place on the mountain, names first as blessed or happy those who are poor in spirit, the truly humble ones, those associated with the humus, the earth. They know the experience of self-emptying as did the God who identifies with humanity (the Emmanu-el/the with-us God). Being poor in spirit as an ecological virtue invites identification with the human community and with the more-than-human Earth community. In this way, God’s new vision for Earth and for the universe can be realised. That vision is imaged in first-century language of the basileia or empire. It is not of Rome or the human community, however, but of the heavens/of the skies. As contemporary readers, our knowledge of “the skies” allows us to hear the image evoking a new understanding of the universe of which the human community is such a small part.

Mourning Broken Relationships

The second beatitude proclaims blessed those who mourn. The extraordinary discovery in an ecological reading of this beatitude is that in the biblical tradition it is not only the human community which mourns but the land also mourns in response to broken relationships in human and other-than-human communities (see Hos 4:3). In particular, we might hear in this beatitude the plight of those Earth creatures who mourn the loss of companions from a species or habitat as a result of destruction by wanton human power. Who, indeed, brings them comfort?

Attending to Earth as Gift

The meek who will inherit the earth evokes Psalm 37 and especially Ps 37:11 which Mt 5:5 cites directly. In that psalm, those who do good or right are those who wait for God (Ps 37:9); those who are blessed by God (Ps 37:22); the righteous (Ps 37:29); and the one who is exhorted to wait for God and keep God’s ways. Each of these phrases could describe the meek whom the psalm says “inherit the earth”. This claim echoes through the third beatitude.

For the ecological reader, however, the language of inheriting the earth needs a prophetic critique because the dominant understanding of land in Israel was that it belonged to God and was given to Israel for its rightful use not its ownership or possession. The ecological reader will attend to and engage with land in its materiality and sociality. It is not simply dirt or ground. It is rich with diversity and relationality and it is a gift.

Living in Right Relationships

The thread that links the third and fourth beatitudes is that of “righteousness” or “the righteous”. In Ps 37:29, it is the “righteous” rather than the “meek” who inherit the land. In the fourth beatitude, those who hunger and thirst for righteousness are called blessed and the righteousness envisaged is the right ordering of all things. For the ecological reader, those who hunger and thirst for this right ordering live in accord with the entire Earth and all its constituents and with divinity. This is the pinnacle of the first four beatitudes and turns readers toward the second group.

Loving Compassionately

The merciful are those named blessed in the fifth beatitude. They embody mercy; one of the key characteristics of God in the Hebrew Scriptures. There mercy is identified as rachamim (womb compassion) and hesed (steadfast love). The merciful whom Jesus proclaims honoured in Mt 5:8 can be understood, therefore, as those who are moved corporeally with womb compassion as God is said to be so moved for the ones who suffer. For today’s ecological reader, suffering is not confined to the human community. Earth itself and all its constituents suffer the ravages of industrialisation, over-farming, dumping of toxic waste, disregard for animals and other devastations. It calls forth the corporeal womb compassion that in its turn can create communities of compassion. It is here that the merciful one is mercied as the beatitude claims.

Openness in Encounters

The honouring of the “pure in heart”, who are promised that they will see God, continues to emphasise the corporeality of the ethics of the Beatitudes. It is with the heart and the eyes that see us as an Earth creature in relation to the divine, as well in relation to Earth and all its constituents. This beatitude seems to call for openness: to God, to one’s own corporeality and to other Earth beings. It is in these encounters that one sees God as God with-us, the Earth community.

Peacemaking

The shalom or the peace of God permeates Israel’s sacred story but there is just one use of the term “peacemaker” (Proverbs 10:10). The peacemaker par excellence in Israel’s sacred story is the ideal king of Psalm 72 who brings together dikaiosynē (righteousness) and peace (Ps 72:3, 7). Jesus proclaims such a one blessed in the final two beatitudes (Mt 5:9,10). The final beatitude then echoes the fourth and adds a recognition that hungering and thirsting and working for right order and righteousness in the entire Earth community can bring persecution.

There are so many arenas in the Earth community where right order has been broken down and relationships destroyed. Each of the Beatitudes gives an invitation or even an imperative for the new vision that frames the Beatitudes (the basileia of the skies — Mt 5:3, 10) while right ordering infuses them through Mt 5:6, 10 (the fourth and eighth beatitude). No longer can we hear this right ordering intended just for the human community. Rather it extends into all relationships in the Earth community. It is this that we hear in the words of the prophet Jesus who sits on the earth of the hillside and teaches.

Published in Tui Motu magazine. Issue 213. March 2017:22-13.