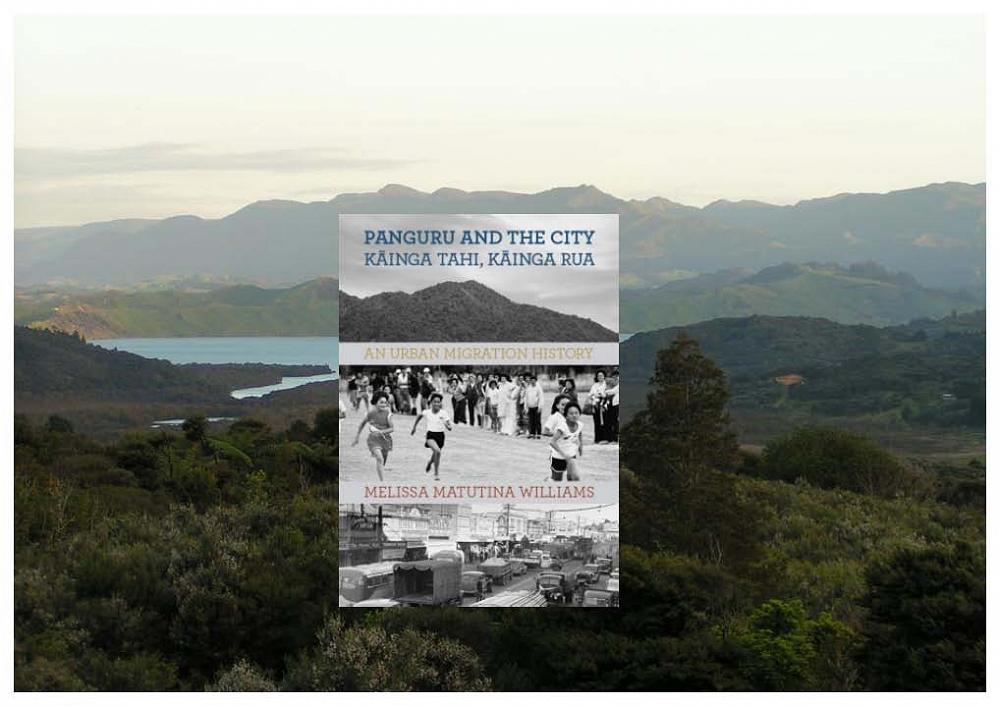

Panguru and the City, Kainga Tahi, Kainga Rua: An Urban Migration History

By Melissa Matutina Williams. Published by Bridget Williams Books, 2015. Reviewed by Susan Smith

Melissa Williams' Panguru and the City, Kainga Tahi, Kainga Rua: An Urban Migration History deserves a wide audience for several reasons. Her trenchant criticism of Pākeha assimilationist ideology that drove government policy in the decades following World War II is an invitation to Pākehā to re-assess their relationship as manuhiri to tangata whenua. Second, Williams' well-researched insistence that migration was always a two-way and carefully thought-out process in respect of movement between Panguru and Auckland deserves careful attention. Third, the role of the Catholic community in Panguru and later in Auckland as the southward movement of Māori picked up momentum was fascinating and eye-opening for this reader. In this review I wish to critique more carefully Williams's observations regarding the Church.

Six small communities — Motuti, Waihou, Whakarapa, Te Karaka, Rangi Point and Mitimiti — are collectively referred to as Panguru whose people belong to the iwi Te Rarawa. Catholicism has always been strong in Panguru, and North Hokianga can rightly be identified as "the cradle of Catholicism". Though there is no chapter in the book called "The Catholic Church in Panguru", as Williams comments "by the twentieth century Catholicism was an inextricable part of community life" (p 15).

Bishop Pompallier along with Marist priest, Catherin Servant and Marist brother, Michel Colombon, arrived in Hokianga in 1838 and although other Marists arrived over the next few years, by the mid 1840s most had moved to the newly established Wellington Diocese. A small number of priests, notably Irish diocesan priest Father James McDonald, continued to respond to the challenge of ministering to the small, scattered Māori communities but it was not until the arrival of the Mill Hill priests in 1893 that a sustained ministry among Māori in Panguru began. The willingness and capacity of the Mill Hill Fathers to become proficient te reo speakers and to grow in their appreciation of Māori culture impressed Panguru whānau. In 1918 adults and children had further important contact with Pākehā when the Josephite Sisters arrived to teach in the parish primary school

How did the meeting of two cultures — Māori and Pākehā — unfold in a remote area where Pākehā were always going to be the minority? This relationship would have its difficult moments. Both groups recognised that future financial security for Māori "depended on their ability to engage with Pākehā people and to adapt to Pākehā culture" (p 46). Through their life with the Sisters in the school, Māori children learnt about that engagement with Pākehā. Although these learning experiences could at times involve feelings of shame and humiliation, nevertheless both groups grew in their appreciation of and mutual need of each other.

The relationship between Sisters and priests continued even when Panguru whānau moved south to Auckland. In 1928, the Mill Hill Fathers began teaching in Hato Petera College in Northcote where they hoped to train catechists to assist them in their ministry. By 1946, it was recognised that an even more pressing need was secondary education for Māori youth. At the same time the movement of young women looking for work in Auckland led to Whina Cooper and the Marist Missionary Sisters working together to open St Anne's Hostel at Herne Bay in 1953. Although some narratives may present Pākehā as the drivers of such initiatives, Williams makes it clear that neither institution could have opened if it had not been for the volunteer labour and fund-raising efforts of whānau both in Auckland and in Panguru.

By the 1960s more Māori were moving south, and the 1962 ordination to the priesthood of Henare Tate (Ngāti Manawa and Te Rarawa), was one of the factors that encouraged Māori to construct an urban marae, Te Unga Waka, at Epsom. This was a massive project involving many whānau from North Hokianga, the Mill Hill priests and women religious. Te Unga Waka provided Māori with a place to "express their faith in te reo at Miha/Mass)" (p 109).

Generally speaking Williams is positive about the relationship between Catholicism and Māori. She approvingly notes Father Henare Tate's observation that "the church reinforced, rather than undermined cultural stability in Panguru" (p 43), this due in no small way to the fact that the Mill Hill priests "made the faith strong in people without interfering in their Māori beliefs or activities" (p 44). The author is clear that priests and sisters involved with Panguru whānau played a key role as cultural mediators. Though she is aware of the cultural misunderstandings that occurred, she is more nuanced, for example, than Māori academic, Ranginui Walker who saw missionaries as "the advance party of cultural invasion” (Ranginui Walker, Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou: Struggle without End 1990, p 85).

Panguru and the City should be read by all those interested in the history of the church in Aotearoa, and in particular, interested in and concerned about the on-going relationship of Maori to Catholicism.