Land and People Crying for Justice, Solidarity and Action

Today we often assume that the boundaries of the land of Jesus and his Jewish ancestors is approximate to that of the recent construct of the State of Israel. This isn't so, but this understanding has contributed to, and can hold in place, the unjust occupation of Palestine by Israel today.

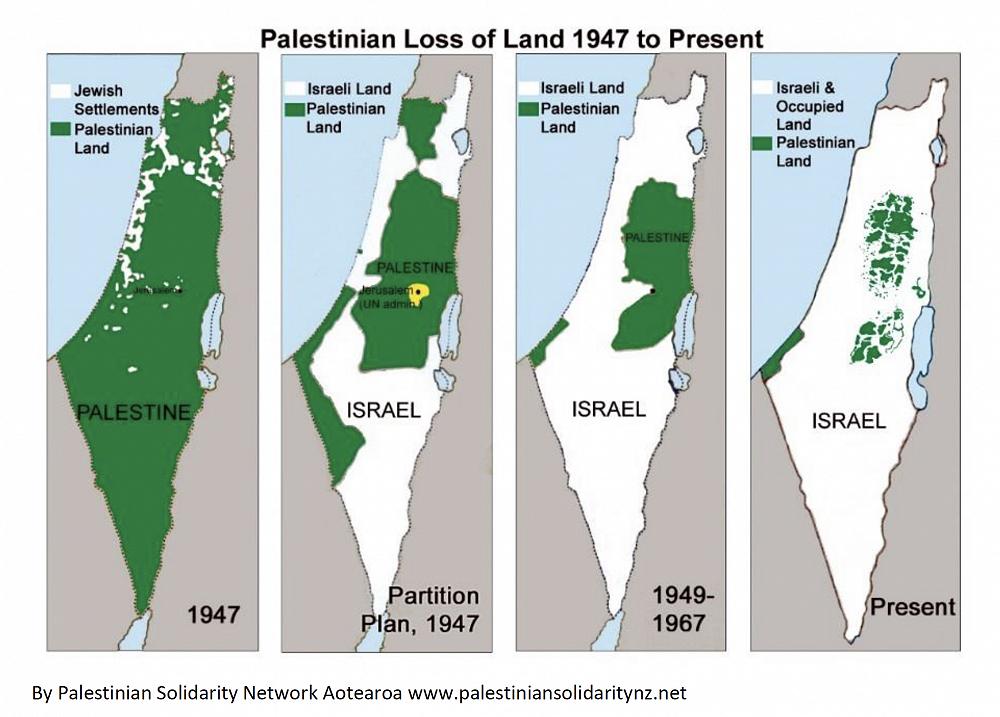

In 1947 the United Nations agreed to partition Palestine into separate Jewish and Palestinian states but directed that this was not to be at the expense of the people — Palestinians — already living there. Earlier in the Balfour Declaration of 1916, the British colonial rulers of Palestine had agreed to support the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine as a “homeland for the Jewish people” but said that nothing should be done which would “prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.” But this has not happened. Once Israel was formed, the Palestinians have been driven relentlessly from their land — despite UN resolutions.

The Biblical Holy Land

The region that gave birth to Judaism and Christianity and has significance for Islam, is often called the “Holy Land”. The name has religious and cultural associations. The actual region was not clearly defined. There are varying accounts of the geographic extent of the land in the OT. At times, some areas are included and others excluded. Certainly, the geographical area known today as modern Israel is not the Holy Land we assume to be Israel in the Bible. The notion of the modern nation state did not exist at that time and boundaries were more fluid.

Abraham, the patriarch promised the land, is revered by the three religions in different ways. But their sacred texts tell us that Abraham owned no land except for a tomb and had little engagement with the population in the area. Later, the land refers to the area into which the Israelites came to settle. But it was called Canaan at the time and was one of the independent city states over which Egypt prevailed.

The Israelites established a tribal kingdom in about 1000 BCE first with David and then Solomon. It was very small. And it was at this time that the people’s oral traditions were written which came to form the biblical Pentateuch. The stories of creation, the patriarchs and the exodus were influenced by the people’s struggle for identity, as well as by the traditions of their more powerful neighbours. They recognised in these events the word and the intervention of their God.

Eventually there were two kingdoms — Israel in the north and Judah in the south. Their near neighbours the Philistines lived between them and the Mediterranean coast.

The term “Holy Land” is found only once in the OT (Zechariah 2:12) referring to the places the Judeans returned to in 538 BCE from their exile in Babylon. But the region of their former kingdom had been divided among the provinces of the great Persian Empire.

“Holy land” in biblical texts refers more to places outside of the kingdom of Israel such as God’s “holy abode” on Mt Sinai (Ex 15:13) and the “holy ground” where Moses encountered God (Ex 3:5).

Bible Is Not History

The bible is not an historical account as we understand history. The writings are imaginative storytelling, theology, ethics and wisdom. It contains books of different literary genres — narratives, epics, oracles, symbolism and poetry — which are woven theologically into the officially sanctioned memory of God’s covenant relationship with the land and the people. Oral traditions evolved across generations into these written accounts. In them we can see the influence of their neighbours’ traditions — repackaged Near Eastern epics and legends, such as the epic of Gilgamesh.

However, the Jewish contribution to the history, the multi-faith and pluralistic heritage of Palestine, is undeniable. We need to respect the particular beliefs and religious sensitivities of Jews, Christians and Muslims. At the same time, we need to understand that beliefs and traditions are not the same as modern history which is grounded in scientific research, critical methodology, historical facts and archaeological research on ancient Palestine.

Palestinian archaeology presents a different reality about the region. It was one of the earliest areas to have human habitation, agricultural communities, civilisation and sophisticated urbanisation. In about 12,000 BCE, the Middle Stone Age, humans began to raise animals and farm the land in the region. Agricultural practices near Jericho date to the Neolithic period, about 11,000-8,800 BCE. Evidence of settlement of the Palestinian city of Jericho goes back to 9,000 BCE, making it one of the oldest continually inhabited cities. According to historians and archaeologists, a stable population existed in Palestine over 6,000 years ago.

The name, Palestine, is continuously found in ancient, medieval and modern histories and historical sources. These include Egyptian and Assyrian inscriptions and texts; classic Greek texts and literature (Palaistine); Roman and Byzantine administrative divisions of the region and sources (Palaestina); medieval Arabic and Islamic sources on Palestine; modern Hebrew (Plelshtina) and all modern European languages and sources. Palestine is inscribed on our New Zealand WWI memorials.

Support for Palestinians

Today, indigenous Palestinians are persecuted, impoverished and treated without human dignity in their own country. The Christian Palestinian movement Kairos Palestine urges the international community “to stand with the Palestinian people in their struggle against oppression, displacement and apartheid.”

We can be informed about their situation, what has led to what they call the Nakba (catastrophe), and take action to relieve their suffering and move towards justice. Their need is urgent. A “Cry for Hope: A Call for Decisive Action” which was launched last year by Kairos Palestine and Global Kairos for Justice, and co-signed by Emeritus Patriarch Michel Sabbah, invites the international Christian community to “engage in study and discernment with respect to theologies and understandings of the Bible that have been used to justify the oppression of Palestinian people.”

We can offer “theologies that prophetically call for an inclusive vision of the land for Israelis and Palestinians, affirming that the creator God is a God of love, mercy and justice; not of discrimination and oppression.”

We can “oppose anti-Semitism by working for justice against anti-Judaism, racism and xenophobia, oppose the equating of criticism of Israel’s unjust actions with anti-Semitism.”

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 260 June 2021: 24-25