‘The single most important thing for teachers to know’: Our approach to the Science of Learning

In January 2017, the influential Welsh educationalist Dylan Wiliam posted this comment on Twitter: “I’ve come to the conclusion that Sweller's Cognitive Load Theory is the single most important thing for teachers to know.”

The Sweller that Wiliam refers to is the renowned Australian educational psychologist John Sweller, who introduced the concept of Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) in 1988. His groundbreaking work, part of the Science of Learning (SOL), drew on insights from cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and educational research. CLT is rooted in the science that we have a limited capacity of memory. It is about how we learn, and retain information, and the most effective teaching methods to maximise this. Sweller argued that teachers need to utilise instruction methods that avoid overloading memory. Knowing how our brains work means that we can develop and use teaching methods and strategies that maximise learning. This is an essential takeaway for teachers. As Sweller states, ‘without an understanding of human cognitive architecture, instruction is blind.’

Since then, we have amassed an important corpus of research studies and an evidence-base, and have moved from theory to a growing coterie of effective techniques to support this. As Peps Mccrea summarises, some of the ideas explored in the last decade are ‘obvious’, while others are ‘deeply counter-intuitive’. They all have the potential to ‘shine a light’ on teaching practice, and as insights, some well developed and others showing promise, contribute meaningfully and impactfully to the learning experience and outcomes of young people in the classroom. What the evidence does show is that students learn best when they are given explicit instruction and opportunities for practice and feedback that they can respond to. Different strategies have been shown by researchers to optimise the load on students’ working memories.

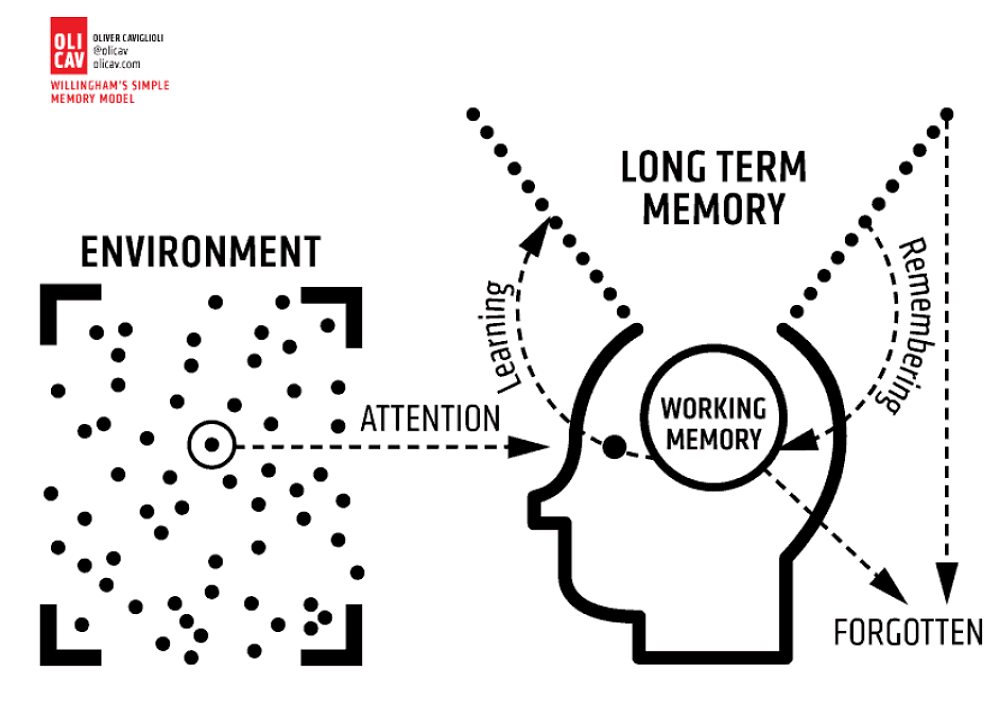

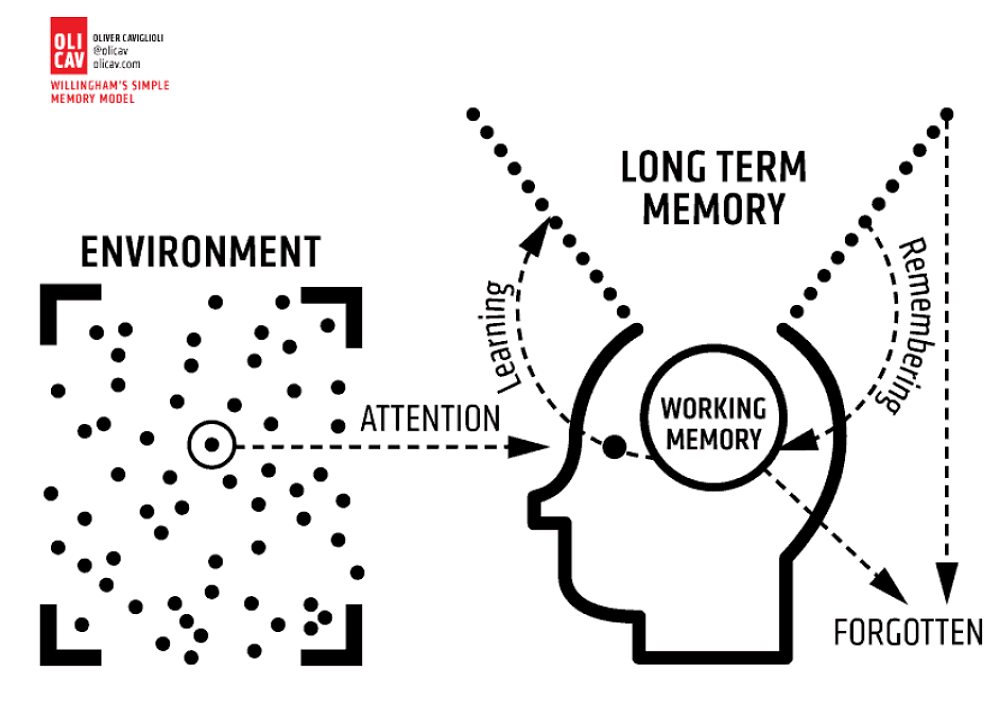

For those unfamiliar with CLT, there are three components of our memory system. We draw on the environment, working memory, and long-term memory, to think. While our attention on the environment and long-term memory are unlimited, working memory is limited. This graphic from Ollie Lovell’s book - Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory in Action - captures these interactions.

Lovell refers to working memory as the ‘bottleneck’ of our thinking. New information takes up more working memory than information we are familiar with. We can reduce the load on working memory by chunking and automating information. Our brains are designed to forget, so it is important to retrieve information from our memory so that we can strengthen (or polish it) it in our long-term memory. This science has an impact on how we should teach in the classroom. The SOL shows that explicit models of instruction are more effective than inquiry-based models.

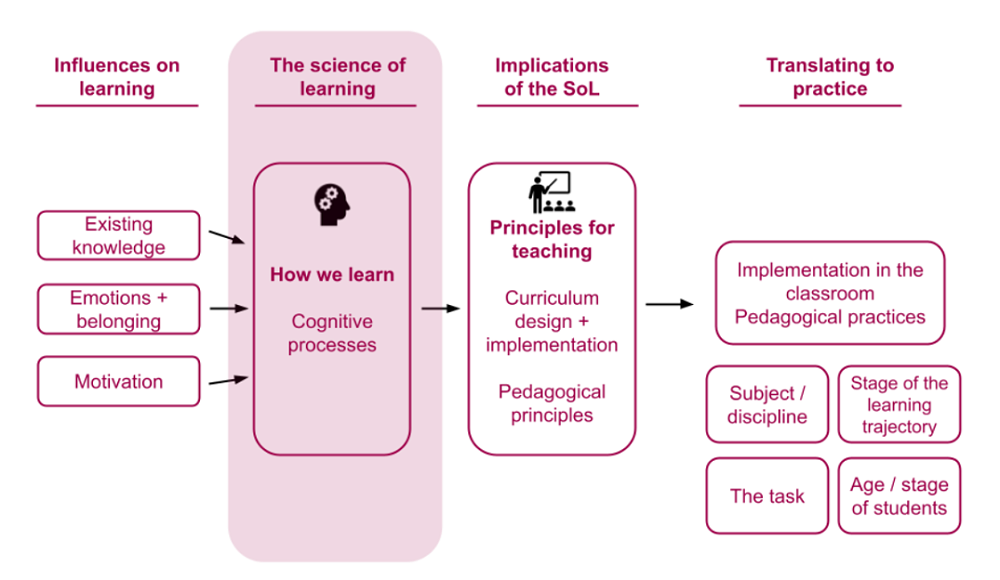

As with any theory or movement in education though, it is important to avoid the pendulum swings and not see the SOL as the curriculum or framework by which we assess. For example, we should not completely move away from using inquiry in the classroom, as there are inherent benefits we can derive from this approach. This was an important takeaway that Dr. Nina Hood shared with us and our Kāhui Ako schools at our annual conference, earlier this year. Nina talked about the implications of the SOL for schools, which she summarised in this graphic.

As Peps Mccrea states, ‘memory underpins learning’. Why then, he challenges, do teachers spend so little time talking about it? We answered this call at Wellington College and have focused a major strand of our collective professional learning and development on the science of learning, and specifically memory, this year. If we can understand how our students learn, we can match this with the most effective teaching strategies.

While the SOL provides a roadmap to how we learn and has implications for the curriculum and pedagogy in the classroom, the most pertinent sphere for us to operate in, is the translation of the theory into practice. This has been a focus for our teachers this year, alongside formative assessment strategies and culturally responsive or sustaining practices.

Bridging the gap between academic theory and classroom practice is a significant obstacle to navigate and no one does that better than Peps Mccrea. To provide a common touchstone for our understanding of memory and its principles for the classroom, we gave all of our teachers a copy of Peps’ excellent book, Memorable Teaching, at the start of the year. In the book, Peps argues that CLT has received a bad reputation at times and has been viewed as the ‘enemy of rich and humane learning’. He sets out to create a coherent framework organised around the ‘decisions of our everyday practice.’ Peps’ framework includes nine principles - manage information, streamline communication, orient attention, regulate load, expedite elaboration, refine structures, stabilise changes, align pedagogies, and embed metacognition. He does a wonderful job of distilling the research into a powerful, quick, and easy read. We thoroughly recommend engaging with this book. You can read a summary of the key takeaways in a reflection included in the first Professional Refresh Annual Collection.

We focused two full-staff PLD sessions on the SOL and memory during Term 3. For the first session, most staff attended a workshop that we called Memory 101. This was intended as an introduction to the theory of CLT and memory. Some staff had attended a version of that workshop at one of the two Kāhui Ako Wānanga

Weeks earlier in the year. To account for their existing knowledge, we ran a Memory 201 workshop alongside the 101 workshop. This was focused on the practical applications of CLT in the classroom.

At the second full-staff session, in the week following, we organised seven workshop carousels and asked staff to opt into two. The intention here was to move from the theory to practical applications. The workshops were facilitated by several teachers and senior leaders and included:

Seven teaching strategies to 'optimise load'

Where relational and SOL meet: The importance of positive learning environments

The implications of SOL for the physical classroom environment

The dark arts of retrieval and dual coding

How SOL and culturally sustaining practices interact to support learning

Using music as a retrieval exercise and tool to create a calm environment

Teaching through worked examples

To support teachers and keep the mahi on top, we’ve focused our Weekly Bites this term on aspects of the science of learning. We include these bites in the SLT Update that is shared with staff each week. These are usually 3-5 minute reads. One piece that we shared was about the limits of the SOL, which was published by CIRL, Eton College’s research centre. Another focused on how teachers can optimise attention in the classroom, and another by Nina Hood about living the science of learning.

The SOL also informs the development of A Learner’s Toolkit, a new initiative we introduced this year. This mahi is focused on developing the study skills and learner habits of our young people. We have partnered with Churchie in Brisbane and are grateful for the open-access resources they create and make available to partner schools. The programme was designed by drawing on the most ‘promising and translatable’ SOL theories. All students have engaged with this learning in Coll Time sessions this year and the Year 11s during their Skills for Life sessions on a Friday.

While the SOL is a facet of the new government’s education priorities, which has put this topic on top for many educators and commentators, as a kura, we have been looking at this mahi for some time and considering its benefits in our context. We are mindful to avoid trends, pendulum swings, or external policy that may not benefit our context, rather we tap into theory and practice that is based on research, is evidence-informed, and might be used to enhance the experience and outcomes for our ākonga. Our approach to the SOL and CLT is considered and we’ve enjoyed pushing into this space with our staff this year, and will continue to as we go forward. As always, we are happy to connect with other educators and share our approach and the resources we have created.

References:

Vicki Likourezos, An introduction to cognitive load theory (The Education Hub, 2021)

Oliver Lovell, Cognitive Load Theory in Action (Published by John Catt, 2020)

Peps Mccrea, Memorable Teaching: Leveraging memory to build deep and durable learning in the classroom (Published by CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017)

Cognitive load theory in practice: Examples for the classroom (NSW Department of Education, 2018)