Seas of Change: Supporting School Leaders in Navigating Change

To achieve our vision for our young people at Wellington College, one of our toughest roles as school leaders is to support staff in feeling comfortable in the discomfort of change—while facing it head-on. We are by no means experts but have learned much along the way about how to gain support in navigating periods of whole-school change in a way that allows staff to feel a sense of security, as well as feeling valued and included.

Change is a movement out of a current state (how things are), through a transition state, and to a future state (how things will be). Change management and change leadership are connected but different, the former relates to how leaders support people through the transitions, while the latter, is about the process of leading people through the transitions. As Viviane Robinson states, ‘to lead change is to exercise influence’ and leave the ‘team, organisation, or system in a better state than before’. As change is hard, so is change leadership and the exercising of influence.

The starting point is to consider why you might introduce a change. In the school context, it will result from one or combination of three directions. Firstly, it might be externally imposed, such as by government policy shifts. A school’s leadership can impose change from within. Change might also result from internal consultation, such as with the staff and the school community. It is key to consider if a proposed change is necessary. If it will have a positive impact on students, then it is.

Our drive to be innovative and transformative at Wellington College has resulted in a busy change context.

Literacy and numeracy co-requisites

Refreshed NZ curriculum

Removal of a L1 NCEA

Formative assessment practices

Values, culture, and character

Relational and restorative practices

Culturally sustainable practices

Learner habits and study strategies

Data practices

Classroom management reset

Rituals and routines

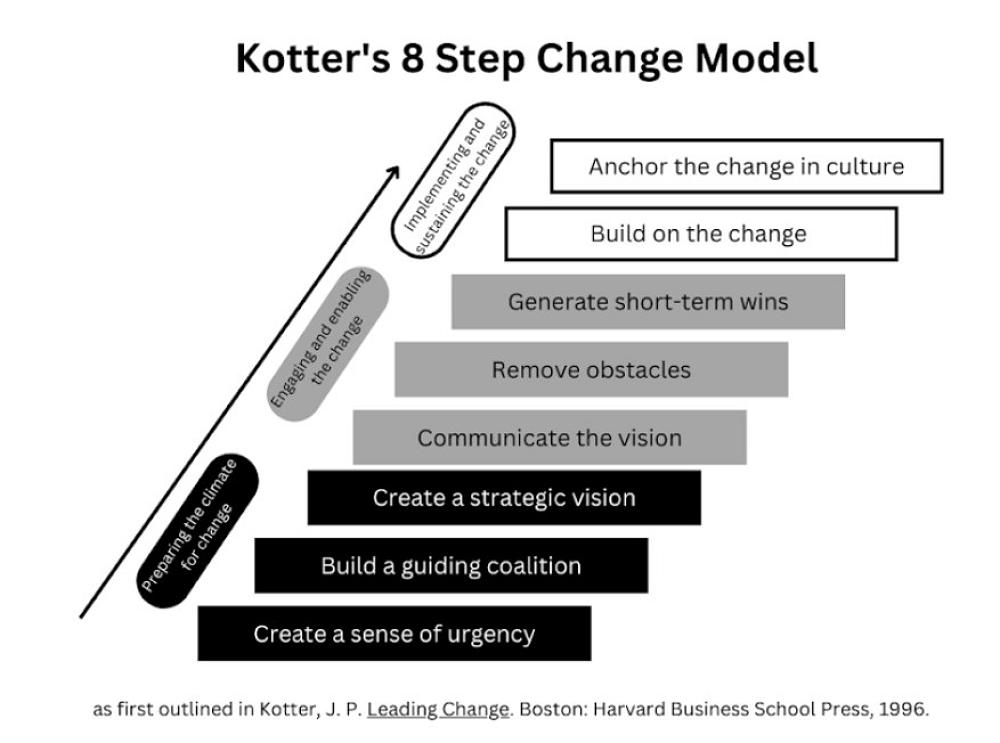

Kotter’s 8-step change model has provided us with a useful theoretical framework.

The challenge of any change journey is the third stage, ‘implementing and sustaining change’. Lotta Tikkanen argues for a top-down-bottom-up implementation strategy, which provides the most effective way to ensure sustainable change. As she explains, this enhances the ‘collective and cumulative’ learning and reduces the burden of those involved in the ‘reform’. We have exchanged ideas with Nicole Billante (Principal at Iona College) about sustainable school development strategies. She advises the following approach.

Why the change? Is there a sense that it’s truly needed? (shared purpose, autonomy)

Mechanisms for collaboration? Is there autonomy or agency in this process? (relatedness, belonging, inclusivity)

Are you celebrating the successes wherever possible? (relatedness, recognising strengths, positive feelings)

Is there a chance to take stock before moving on to next phases? (competence)

A key question when initiating change relates to consultation. Robinson emphasises the importance of avoiding the ‘trap’ of superficial consultation, and argues that you should ‘engage deeply’ in a discussion about values, beliefs, and actions, from which you arrive at a co-designed and shared ‘theory of action’. We have found that there are varying degrees of consultation and that you judge this individually for each initiative or activity. We assess each change for the level of consultation that will support its introduction and implementation. Using a guiding coalition or working group when it is not practical or desirable to consult more widely is also effective. We also make our peace with the fact that sometimes, leaders need to make decisions and lead.

Change is hard, and made harder by a period of myriad changes. We recognise this at Wellington College. It presents challenges in bringing people along and achieving the vision. We hold close to Berger and Johnston’s comments that ‘in times of complexity, it is useful to admit you don’t know the answers, but that you are learning rapidly’. Although we acknowledge that we are not experts, we have learned a few things. At the heart of this is our curiosity, openness, authenticity, and courage, which provide the foundations by which to navigate the seas of change.

The hard part is embedding change

Martin Matthew is right in his comment that the final stage of embedding change is ‘easier said than done’. You need to, he explains, continue to empower people to continue to implement change. Firstly, think about how to support and guide middle leaders, as they are closest to the action and the key to any change being embedded. Then think about how people might be held to account. Change is unsettling and there will be people who are reticent to that change. Connectedly, how will you support people finding the change difficult? These will oftentimes be the same people reluctant to engage with the change.

Enable leaders and change agents

As mentioned above, middle leaders play a crucial role in embedding change. They need to be enabled to lead in their area, which involves providing them with the right tools and supports and clearing away obstacles. Growing leaders is a key responsibility of a senior leadership team. Sharing the approaches to change and strategy that you value and need gives a powerful boost to the change journey. We achieve this at Wellington College through our leadership institute, which provides a structured programme of learning about leadership that supports our messaging about change. Finally, find the positive influencers and empower them to champion the change.

Support people through change

Dottin states that a teacher's disposition toward change is based on both their ‘desire’ to enact the change and their ability. Two key questions drive the response here, the first, is what do staff need to deliver the change? Secondly, what do they need right now to do a better job? This serves to address the basic psychological needs that Deci and Ryan state as autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which are required for motivation, development, and wellbeing.

Pacing and prioritising

This connects to supporting people through change and requires flexibility, principally around timelines. If time is an obstacle then remove it. Phil Wood comments that too often, education contexts assume that transformation comes by speed and demonstrations of ‘radical change’. Rather, ‘true transformation’ is ‘quiet, evolving, and communal’. Go slow, as old habits need to be unlearned and people’s cognitive load managed. This sits alongside the constant communication and management of priorities. While our leadership team might be working on four initiatives, we only place the one that requires peoples’ immediate attention, and energy efforts, in front of them. This also lightens change fatigue.

How to navigate change fatigue

Change fatigue undermines progress towards the vision but can be mitigated. We adhere to Tikkanen’s top-down-bottom-up approach, which gives a sense of ownership to all stakeholders. Distributed leadership plays a key role and enables and trusts middle leaders to lead. Patrick Palmer talks about living in the ‘tragic gap’, which reflects the tensions between possibility and reality. This requires patience, anticipation of the bumps, and permitting imperfection. The true superpower is leading with courage and compassion. Consider what it looks like in the back of the room because as leaders, we know what it looks like in the front.

It is also about where you place your energy. Responses to change will inevitably fall into three brackets. Using the train analogy, the early adopters will head to the front carriage. We have them with us already, so promote them as influencers, but they don’t need convincing. A group reluctant or opposed to the change will head to the third carriage, while most people will sit in the middle carriage. Focus your efforts on the middle carriage as they can be brought along.

Consider your wellbeing (as a leader)

It is important to recognise that as leaders we represent a threat during a period of change. We shoulder the anxiety and stress of others. This can test your instincts and judgments. While we feel the tide turning at Wellington College, we have experienced bumps and tensions during our change journey. The key is to respond and not react, particularly if you are being led by emotion. Leaders are human too and feel tension, stress, and conflict like anyone else in the organisation. Most importantly, draw on your support, whether it is other members of your leadership team or colleagues outside your school. As Stephen Covey preaches, ‘sharpen your saw’ and maintain a balance in your body, mind, heart, and spirit, so that you are renewed and refreshed and ready to face the challenges of the change journey.

Be a research-invested school

A research-invested school embraces research and innovation as key to its identity and mission and supports teachers to consume, apply, and generate knowledge. We ensure that our decisions are based on evidence and research and foster a research culture. Share digestible and relevant research with people as a support tool and encourage knowledge generation to address local problems. We achieve this through a professional reading initiative and action research programme, as well as normalising sharing and engaging with reading. We also forge external partnerships and go to the well of other contexts for best practice and bring that back to our kura.

For true change, go all in

We hold these tenants close as we navigate the seas of change, which synthesise the learnings that we have shared above.

Begin with the end in sight

Identify a champion(s)

Add by subtracting

Ensure deep knowledge

Plan; try, test, and improve

Listen to teachers and students

References

Jessica Dilkes et al, ‘The New Australian Curriculum and Change Fatigue’, Australian Journal of Teacher Education, Vol.39, Issue 11 (2014)

Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation development and wellness (Guilford Press, 2017)

E. Dottin, ‘Professional Judgment and Dispositions in Teacher Education’, Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(1) (2009)

Jennifer Garvey Berger and Keith Johnston, Simple Habits for Complex Times: Powerful Practices for Leaders (Stanford Business Books, 2016)

John Kotter, Leading Change (Harvard Business School Press, 1996)

Martin Matthew, ‘Leading Change in School’, SecEd, No.9 (2018)

Viviane Robinson, Reduce Change to Increase Improvement (Corwin publishers, 2017)

Lotta Tikkanen et al, ‘Lessons Learned from a Large-Scale Curriculum Reform: The Strategies to Enhance Development Work and Reduce Reform-Related Stress’, Journal of Education Change, Volume 21 (2019)

Phil Wood, ‘Overcoming the Problem of Embedding Change in Educational Organizations: A Perspective from Normalization Process Theory’, BELMAS, Volume 31, Issue 1 (2017)